Invasion of Scheinfeld

| Invasion of Scheinfeld | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

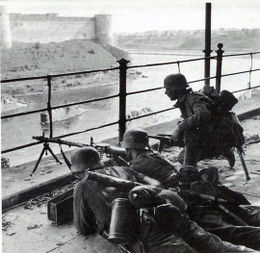

A Rotgeheiman machine gun team provides overwatch on a bridge overlooking a river, 14 May 1916 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

Rotgeheiman armies

Noard-Holland armies

| Scheinfeld armies

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Rotgeheim: 65 divisions, 27,000 guns, 14,000 tanks, 6,000 aircraft Noard-Holland: 12 divisions, 5,000 guns, 2,000 tanks, 5,000 aircraft Total: | Scheinfeld: 41 divisions, 9,000 guns, 3,000 tanks, 4,000 aircraft Total: 820,000 |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Rotgeheim: Noard-Holland: | Scheinfeld: | ||||||

The Invasion of Scheinfeld, also known as the Spring Campaign (Rotgeheiman: Frühlingfeldzug), and alternatively Operation Weigela (Rotgeheiman: Unternehmen Weigelien), was a joint invasion of Scheinfeld by Rotgeheim and Noard-Holland. The invasion began on 16 April 1916, several weeks after the signing of a pact between Rotgeheim and Noard-Holland, and ended on 20 May with Rotgeheim and Noard-Holland dividing occupation control over the whole of Scheinfeld.

Contents

Prelude

Scheinfeldian conspiracy against Rotgeheim

In 1914, Rotgeheim came under attack by the military of Fuerstenburg in its northernmost province of Finnmarck in what was to be later known as the Northern Territory War. Rotgeheim, since the majority of its military units were on the Rotgeheiman mainland, and the ones in Finnmarck were vastly overwhelmed by invading forces, appealed to several nations for help. In mid September, Kaiser Rudolf Geske issued a formal plea for military assistance to several nations, including Northern Prussia and Scheinfeld, both of which had strong ties to Rotgeheim. Northern Prussia agreed to dispatch men and materiel to assist the beleaguered Rotgeheiman forces, but Scheinfeld unexpectedly refused. The unwillingness for Scheinfeld to assist Rotgeheim during its time of need was both shocking and disappointing to Rotgeheim. However, Scheinfeld had no obligation to provide assistance to Rotgeheim, so Kaiser Geske was forced to pursue the issue no further.

In June 1915, as the Northern Territory War neared conclusion, intelligence gathered from Rotgeheiman operatives in the field concluded with absolute certainty that enemy forces were engaging Rotgeheiman troops with equipment supplied by Scheinfeld. In an international conference held on 18 July, Rotgeheiman ambassadors and envoys publicly presented the allegations that Scheinfeld had been at least partially fueling the conflict in Finnmarck. Scheinfeld denied the accusations. The Scheinfeldian ambassador stated that the equipment utilized by Fuerstenburg was purchased years prior to the conflict, and Rotgeheim did not have the authority to make decisions on who gets to trade with what nation, even if the equipment had been supplied during the conflict.

Tensions continued to rise between Rotgeheim and Scheinfeld through the following months. When the Northern Territory War concluded in September 1915, Rotgeheiman military officials came forth with new evidence accusing Scheinfeld of supplying materiel to Fuerstenburg forces. Several Fuerstenburg armored vehicles recovered from battlefields had been of Scheinfeld origin, but it was later confirmed that certain variants used in combat were types that had been introduced in early 1915. These types had to have been supplied by Scheinfeld in the middle of the conflict, and the discovery of this vehicles confirmed with absolute certainty that Scheinfeld had not only sold military hardware to an enemy of Rotgeheim, but actively denied in doing so.

After this discovery was brought to light, Kaiser Geske immediately began campaigning for sanctions to be placed on Scheinfeld. Several government members advocated for an invasion of Scheinfeld to eliminate the threat it posed to Rotgeheiman sovereignty, citing the sale of weaponry to enemy nations as an act of aggression in itself. Rotgeheim formally imposed sanctions on Scheinfeld on 2 October 1915, with Northern Prussia following on 9 October.

Building tension

Although many Rotgeheimers advocated for war against Scheinfeld, Rotgeheiman leadership was initially unwilling to jump into a conflict right after finishing one. However, a series of aggressive actions by Scheinfeld greatly agitated relations between the two countries, pushing them ever closer to war.

On 22 January 1916, a Rotgeheiman civilian shipping vessel in international waters became the victim of stalking by an unknown number of Scheinfeldian submarines. Although the Rotgeheiman freighter was civilian, the Scheinfeldian submariners assumed it was a military vessel and pursued it for almost fifty nautical miles. It was later revealed that the Scheinfeldian submarine pack was acting under orders to usher any Rotgeheiman military vessels away from common Scheinfeldian shipping lanes, believing the Rotgeheiman navy to be the largest threat to marine trade. The Rotgeheiman reaction to the incident saw complements of hired guns being stationed on many civilian ships, and the government imposed more sanctions than before. Scheinfeld replied with its own set of sanctions, although they were entirely ineffective.

As a counter to the increased presence of Scheinfeldian military vessels in international waters, the Navy of Rotgeheim began attaching gunboats and even destroyer escorts to groups of civilian merchant ships. Scheinfeldian submarines did not back down from stalking Scheinfeldian merchant convoys, however. The naval buildup on international shipping lanes served only to agitate maritime problems, producing several standoffs between opposing naval forces that wished to occupy the same shipping lanes.

The aggressive nature of Scheinfeld's maritime policies culminated in the Sinking of the Lüsebrinck on 9 April 1916, where a merchant vessel carrying humanitarian aid resources was sunk by a Scheinfeldian submarine. Rotgeheim, as well as many countries around the world, were outraged. In the days following the sinking, Rotgeheimers lobbied outside government buildings across the country to declare war on Scheinfeld.

Opposing forces

Rotgeheim

Rotgeheim had a significant numerical advantage over the defending forces of Scheinfeld. Altogether, Rotgeheim had 65 divisions organized into two army groups, clocking in at a grand total of roughly 1.2 million troops. Rotgeheim had a severe advantage in armor and artillery, with 14,000 tanks and nearly 27,000 guns and howitzers. New operational doctrine developed during the 10 Days War for armor units was again utilized during this conflict with just as much success. Armor divisions, acting as the tip of the spear, punched holes in enemy lines which were to be quickly filed by mechanized infantry. The infantry and flanks of armor would then encircle and destroy pockets of enemy troops, while the main armor thrust continues on.

Air power of Rotgeheim also played a significant role. Although the Scheinfeldian Air Force was of lesser number, the aircraft still posed a major threat. Nearly 6,000 aircraft of all types were amassed to take part in the invasion to counter the Scheinfeldian Air Force.

Noard-Holland

Although smaller than the other two belligerents, Noard-Holland was a militarily formidable country. 12 divisions of crack soldiers organized into three armies that make up nearly 325,000 soldiers. The Noard-Holland armies were also equipped with over 5,000 guns and howitzers, and 2,000 tanks. The Noard-Holland Air Force committed over 5,000 aircraft, mainly focusing on dive bomber and fighter craft, which plagued Scheinfeldian positions during the war.